For children, adequate nutrition is crucial for good health and brain development in their formative years. Accordingly, food insecurity, defined as the “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods,”[1] can have significant long-term health effects on children. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity has reached record highs, particularly in Black, Latinx and Indigenous households. In 2019, the USDA estimated that 35.2 million people lived in food insecure households, including 10.7 million children.[2] Among these food insecure households, 361,000 children experienced very low food insecurity, meaning that “the food intake of household members was reduced and their normal eating patterns were disrupted because the household lacked money and other resources for food.”[3]

In 2020, food security worsened for millions of American children as the coronavirus spread and rates of unemployment, economic, health and social challenges skyrocketed.

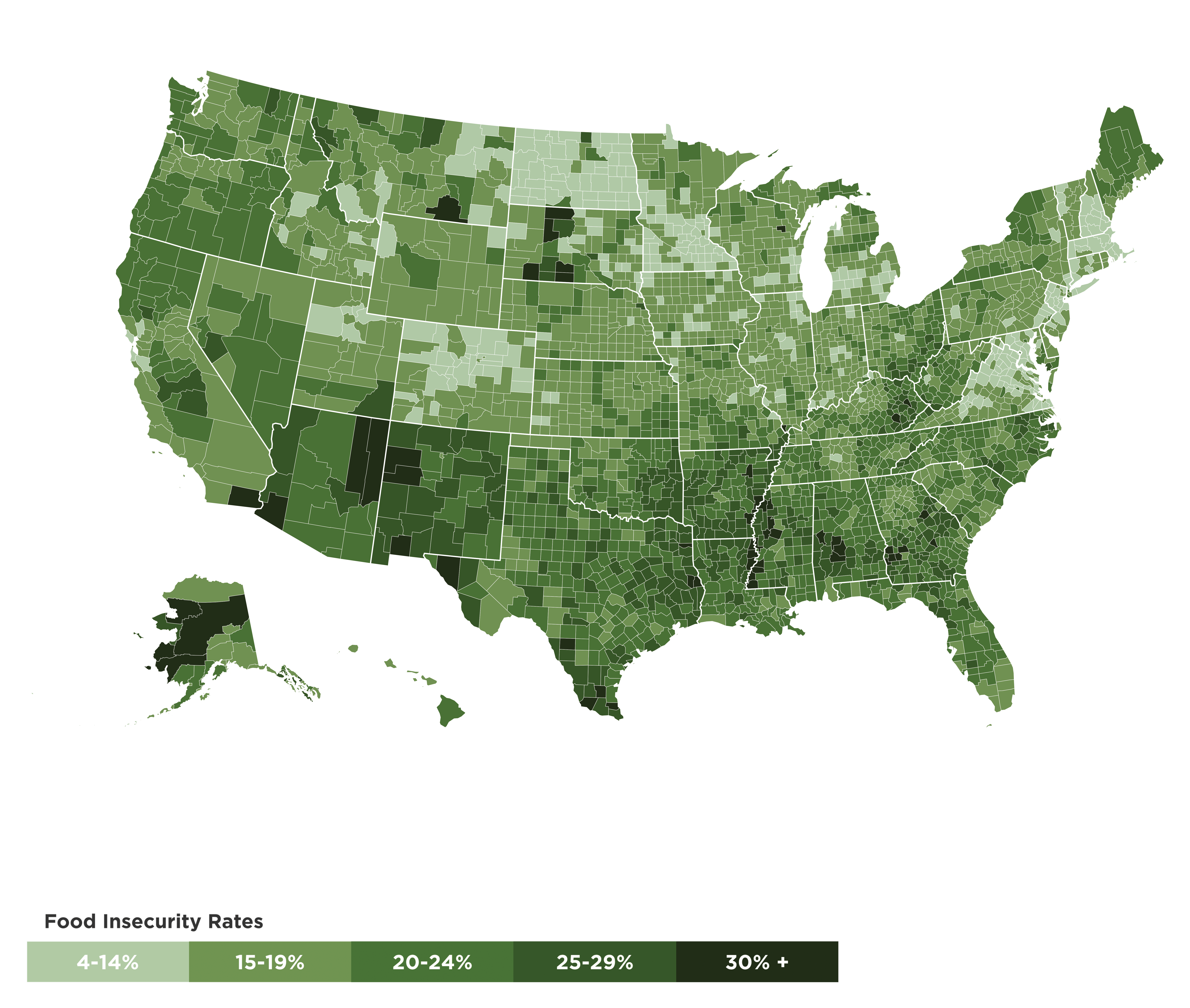

Child Food Insecurity Rates by County:

According to projections from Feeding America, approximately 1 in 4 children, or 17 million children in total, were food insecure in 2020.[4] Further, additional research collected by the Urban Institute highlights the significant hardships Black and Latinx households with children are much more likely to experience than white households. Through their Coronavirus Tracking Survey, conducted September 11–28, 2020, the Urban Institute found that Hispanic/Latinx parents and Black parents reported experiencing food insecurity at almost triple the rate of families with white parents. Additionally, the Urban Institute found that 36.9 percent of Hispanic/Latinx parents and 29.6 percent of Black parents reported being worried about having enough to eat in the next month, compared to 9.6 percent of white parents. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Black and Hispanic households reported rates of 19.1 percent and 15.6 percent, respectively, although the national average was 10.5 percent.

The negative consequences of hunger and food insecurity among children are well-documented. Hunger is associated with a higher risk of chronic diseases, particularly asthma, and also with a range of behavioral, social and mental disorders.[5] In addition, a lack of adequate nutrients, such as iron, zinc and vitamin A, impairs the ability of children to learn, undermining academic performance and achievement.[6] Missing meals and experiencing hunger also impairs school performance and behavior at school. Hungry children earn lower grades, are more likely to repeat a grade and have higher rates of tardiness and absenteeism.[7] On the other hand, children who participate in the School Breakfast Program (SBP) have increased academic performance, fewer behavior problems and better attendance records.[8] Further, a recent paper from the Brookings Institution noted that students who ate healthy lunches at schools increased their end-of-year test scores.[9] For students who qualified for free and reduced-priced lunch, test score increases were 40 percent larger than those observed for students who were not eligible for free and reduced price meals.[10]

Federal nutrition assistance programs are critically important investments that support the long-term health and well-being of infants, children, mothers and families. Extensive research shows that WIC improves the nutrition and health of low-income families, resulting in safer pregnancies for the mother and child, healthier newborns and food-secure children.[11] Similarly, SNAP not only lifts millions of people out of poverty each year, but also improves child health and development. Research has shown that SNAP participation is associated with an increased likelihood of completing high school and a decreased likelihood of a child becoming obese as an adult.[12] Further, the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs have been proven to decrease food insecurity, improve dietary intake and reduce obesity.[13] In 2015, USDA found that children receiving free or reduced-price lunches through the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) had increased consumption of milk, fruit and vegetables, as well as increased consumption of calcium, Vitamin A and zinc and lower consumption of empty calories.[14]

Policy | Direct Certification for School Meals

Background on Policy - School Meals

The NSLP and SBP are the primary federal child nutrition programs. Schools participating in NSLP and SBP provide children nutritionally balanced meals in accordance with USDA dietary guidelines. Children who come from families with incomes of less than 130 percent of the federal poverty guidelines receive free meals through NSLP and SBP, while those from families with incomes between 130 and 185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines receive reduced price meals.

Policy Description - School Meals

Congress has established direct certification for free school meals for certain categories of children whose families are most likely to struggle with hunger. Through direct certification, school districts match enrollment records with the names of children living in households that receive SNAP and other allowable programs. This match is then used to approve students for free school meals without the need for their families to complete a school meals application. A number of steps have already been put into the law to allow more children eligible for free meals to be directly certified. For example, in 2008, school systems were required to conduct data matches to directly certify children in households participating in SNAP. Starting in 2012, Congress began to allow states to use Medicaid participation to directly certify income-eligible children for free meals.

However, there is ample room to improve direct certification to ensure that eligible, low-income children can receive free meals through the NSLP and SBP. The following policies would expand this important simplification tool to more vulnerable children who are already eligible for free school meals and strengthen the process for those households that are already permitted to be directly certified but often miss out. Although many children are eligible for free or reduced-price meals based upon their families’ income, many families are unaware of their eligibility and thus do not receive the NSLP benefits to which they are entitled under the law.

- Directly certify all low-income school-age children receiving Medicaid: The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 established a demonstration project that expanded direct certification to children enrolled in Medicaid and whose household income is below 133 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. At present, only 19 states are operating the Medicaid direct certification demonstration project. This policy would expand this policy to all states, requiring all income-eligible children participating in Medicaid to be directly certified for free school meals.

- Expansion of Mandatory Direct Certification: Currently, school districts are required to directly certify students living in households participating in SNAP. Other vulnerable children, such as those receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance, children in foster care or Head Start and children who are homeless, runaway or migrant are automatically eligible for free meals. However, the decision to directly certify these children is left to the discretion of a school district. This policy would require school districts to utilize this important simplification tool to reach these children, in addition to those receiving SNAP benefits.

Policy | Strengthen the Community Eligibility Provision

Background on Policy - Community Eligibility

The Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) allows high poverty schools to offer school breakfast and lunch at no cost to all students. Any school district, group of schools in a district or individual school can participate in CEP if 40 percent or more of the students are categorically eligible for free meals (e.g. receive SNAP, TANF or other eligible programs). Referred to as “identified students,” these children represent the population of students who would qualify for free meals without an application.

CEP has transformed the school nutrition programs, allowing more students to experience the educational and health benefits linked to school breakfast and lunch participation, significantly reducing administrative work for schools and families and eliminating unpaid school meal debt. Equally as important, CEP allows all students to receive the same meals regardless of income level, eliminating stigma and increasing students’ access to healthy meals.

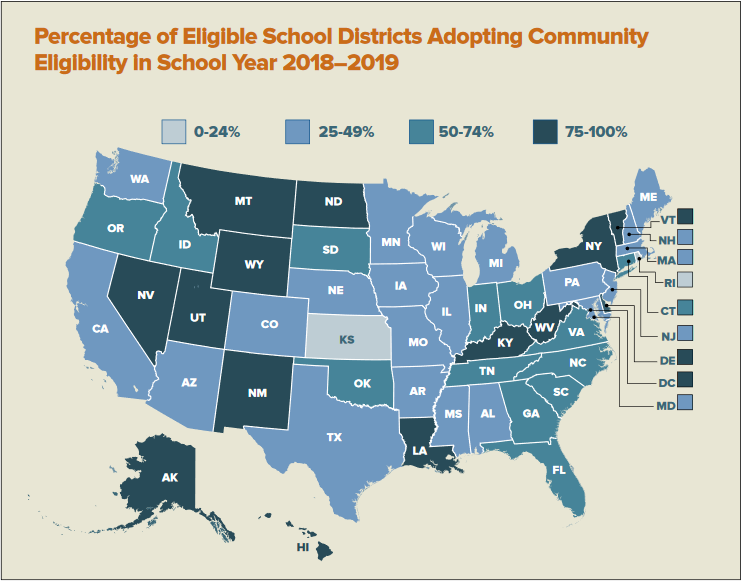

Since CEP was introduced, its benefits for families, schools and low-income communities have led to widespread adoption. More than 14,000 schools adopted CEP when it first became available nationwide in 2014. Since then, nearly 28,500 schools, representing approximately 65 percent of eligible schools, have adopted CEP. In the 2018—2019 school year, 13.6 million students attended schools that offered meals at no charge as a result of CEP.[1]

Under current law, schools are reimbursed based on the share of “identified students,” or the percentage of children who are categorically eligible for free meals. The “identified student percentage” (ISP) is then multiplied by 1.6 to determine the percentage of meals that will be reimbursed at the free rate. For example, a school with an ISP of 50 percent would be reimbursed for 80 percent of meals at the free reimbursement rate (50 percent x 1.6 = 80 percent) and 20 percent at the paid rate.

Despite the expansion of CEP, opportunities remain to strengthen CEP to enable more eligible schools to offer universal meal access, allowing school districts to focus on providing nutritious food rather than processing unnecessary paperwork.

Description of Policy - Community Eligibility

Increase the community eligibility reimbursement. Schools are far more likely to adopt CEP if their ISP is above 60 percent. For schools with ISPs below 60 percent, the percentage of eligible schools adopting CEP drops from 80 percent to as low as 20 percent.[1] This policy would increase the CEP reimbursement multiplier from 1.6 to 2.5. Increasing the reimbursement multiplier would make it easier for eligible schools to cover their costs while foregoing meal fees.

Allow community eligibility school groupings across districts. Under current law, school districts decide whether to adopt community eligibility for all or some of their schools. This policy would establish a demonstration project that would allow federal reimbursements for community eligibility to be determined across school districts, potentially even statewide. Giving local education agencies more flexibility to group similar schools together will increase and improve the ability of school districts to increase the number of schools that can directly certify low-income children, thus increasing the number of children who are able to participate.

Policy | Retroactive Reimbursement for School Meals

Background on Policy - Retroactive Reimbursement

School lunch shaming and stigma are issues that have gained considerable attention in recent years. This shaming and stigma typically occurs when a student accrues some degree of unpaid school meal debt and a school district decides that a student may no longer receive school meals until the debt is paid. In the most extreme cases, parents of children with school meal debt have been threatened with court appearances and the possibility that their children might be put in foster care.[1] While this is an extreme case, it is not unusual for children with unpaid debts to lose access to schools meals. In such a case, children are often given an alternate meal, such as a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Not only is this often insufficient to meet children’s nutritional needs, it also singles out such students and publicly reinforces their economic need relative to other students.

Description of Policy - Retroactive Reimbursement

Many of the students who accrue meal debt are eligible for free or reduced-priced meals but are not certified for such meals for a number of reasons, including language barriers, poor administrative processes or lack of robust direct certification procedures. Retroactive reimbursement for children who are eligible for free or reduced-price meals, but who are not certified until later in the year, would increase school meal participation, reduce school meal debt and eliminate the stigma associated with children being singled out as a result of their meal debt. Under current law, USDA allows local educational agencies to go back to when they received direct certification information or when the family submitted an application, but no earlier. This policy will expand the time period for retroactive reimbursement and allow for such reimbursement to go back to the beginning of the school year.

Expected Impact of Policies

Broadly, these policies will result in many more children participating in school breakfast and lunch with less administrative burden. Among other improvements, they will specifically result in the following:

- More eligible children will be certified to receive free school meals. Direct certification eliminates the barriers experienced by some families filling out a school meal application, such as literacy or language barriers.

- Fewer students sitting in classrooms hungry. Community eligibility eliminates the stigma often associated with participating in school breakfast and lunch, resulting in increased participation among low-income students. It also allows students who are eligible for reduced-price meals to receive free meals at school.

- Less administrative work for schools. School districts now spend a significant amount of time processing school meal applications. Direct certification reduces the number of school meal applications a district will have to process, saving the district time and money. Similarly, improved community eligibility means that instead of spending significant time processing school meal applications, schools can focus on providing healthier meals to more students.

- Improved program impact. Direct certification uses a child’s participation in federal means-tested programs or a child’s high-risk status (such as being homeless or in foster care), thus ensuring that the child is eligible for free school meals.

- Reduced school meal debt and stigma. Schools that adopt CEP do not need to collect meal fees or follow up with families who have accrued school meal debt. In addition, retroactive reimbursement for children will significantly reduce school meal debt, as well as the stigma attached to children who accrue school meal debt and, as a result, are no longer eligible to receive meals through the National School Lunch or School Breakfast Programs.

In addition to other benefits, including less administrative work and improved program integrity, expanding direct certification and community eligibility moves the National School Lunch and School Breakfast Programs much further in the direction of universal meal service, especially in schools with significant proportions of low- and moderate-income students. This, in turn, will move school meal programs away from income-dependent requirements and toward universal benefits for all children. In so doing, children will not only experience significantly greater freedom from hunger and poor nutrition, but schools will gain more capacity to focus on their core functions of teaching students, as well as being freer to attend to the complete array of children’s educational needs.

[1] Amir Vera, “Pennsylvania school district tells parents to pay their lunch debt, or their kids will go into foster care,” CNN, July 21, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/07/20/us/pennsylvania-school-lunch-debt-trnd/index.html.

[1] Ibid.

[1] Alison Maurice et al., Community Eligibility: The Key to Hunger-Free Schools (Food Research & Action Center (FRAC), May 2019), https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/community-eligibility-key-to-hunger-free-schools-sy-2018-2019.pdf.

[1] “Measurement: What is Food Security?...and Food Insecurity?”, (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, September 2019), https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement/#insecurity.

[2] Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Insecurity in the United States in 2018” (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, September 2019), https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/94849/err-270.pdf?v=963.1.

[3] Ibid.

[4]The Impact of the Coronavirus on National Food Insecurity in 2020 & 2021 (Food Research & Action Center (FRAC), 2021), https://www.feedingamerica.org/research/coronavirus-hunger-research.

[5] The Impact of Poverty, Food Insecurity, and Poor Nutrition on Health and Well-Being (Food Research & Action Center (FRAC), 2017), https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/hunger-health-impact-poverty-food-insecurity-health-well-being.pdf.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Facts About Child Nutrition,” January 2020, National Education Association, http://www.nea.org/home/39282.htm.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Michael L. Anderson, Justin Gallagher, and Elizabeth Ramirez Ritchie, “How the quality of school lunch affects students’ academic performance,” May 3, 2017, Brookings Institution Brown Center Chalkboard, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/05/03/how-the-quality-of-school-lunch-affects-students-academic-performance/.

[10] Michael L. Anderson, Justin Gallagher and Elizabeth Ramirez Ritchie, School Lunch Quality and Academic Performance (National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2017), https://www.nber.org/papers/w23218.pdf.

[11] Steven Carlson and Zoë Neuberger, WIC Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income Families for 40 Years (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 20, 2017), https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wic-works-addressing-the-nutrition-and-health-needs-of-low-income-families.

[12] Long-Term Benefits of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (The Obama White House, 2015), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/files/documents/SNAP_report_final_nonembargo.pdf.

[13] Katherine Ralston and Alisha Coleman-Jensen, “USDA’s National School Lunch Program Reduces Food Insecurity,” August 1, 2017, United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2017/august/usda-s-national-school-lunch-program-reduces-food-insecurity/.

[14] Ibid.